12.09.10

12.09.10

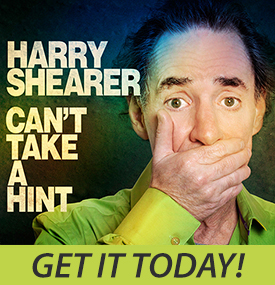

Yves Smith Interview #1

Transcript – Le Show Interview with Yves Smith

Here it is!

From deep inside your radio.

HARRY SHEARER: This is Le Show. For the last few months I’ve been reading and learning from a blog on matters economic called Naked Capitalism and sharing some of the tidbits I’ve gleaned therefrom with you on this program, and I thought today would be educational for both me and you to have the author of this blog on the program to guide us through this thicket of the foreclosure mess, a thicket which seems to be thickening as we speak. So I’m welcoming to the Le Show Yves Smith, author not only of the blog Naked Capitalism but of the book ECONned. Yves, welcome.

YVES SMITH: Harry, thanks so much. My pleasure to be here.

HARRY SHEARER: And I have to say, first of all, it came as a surprise a couple months into reading your blog, when I discovered through a video interview of you that though you spelled the name Yves, you are in fact a female.

YVES SMITH: That’s correct. I actually started out with that nom de blog precisely because every study ever done shows that if you take the same writing sample and attribute it to a male name versus a female name, it will be better perceived, and with the internet you at least initially have the advantage of anonymity. There’s this joke that, you know, somebody who’s writing on the internet could be a 14-year-old or a dog.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: Obviously I’m hope–

HARRY SHEARER: Hopefully neither.

YVES SMITH: I’m hopefully neither.

HARRY SHEARER: Yeah.

YVES SMITH: But, you know, you can sort of muff things for a while if you want to, and there is a proud tradition of people writing under things that are more obvious pen names than the one I use.

HARRY SHEARER: Well, I – I’m almost embarrassed to say this, but I have to say it, you write like a man.

YVES SMITH: (laughs) Well, thank you.

HARRY SHEARER: I don’t know if I should be thanked for that, but there it is. Anyway, so in real life, aside from blogging, what is it that you do that brings you into this world?

YVES SMITH: Well, I’m a bit of a hybrid. I’ve actually been involved in the financial services industry for, I hate to say, 30 years. I started out on Wall Street at Goldman Sachs in corporate finance, which is the part of the business that’s involved in helping large companies raise money. Then I went to McKinsey and worked in their financial institutions group almost entirely again for big global financial firms, then was recruited by one of my clients, Sumitomo Bank, to start up their U.S. mergers and acquisitions department in the days when Japan looked like it was taking over the world and that looked like an exciting thing to do. That quit making sense in 1989 for a whole bunch of reasons, and I’ve had my own consulting practice since then, and I’ve, you know, again, continued to work a lot with major financial institutions as well as hedge funds and substantial private individuals. The financial institutions has actually gotten me into some trading floor work, so I’ve just wound up by where my assignments have taken me of getting my nose under the hood of a lot of different, sort of, subbusinesses in the financial services industry.

HARRY SHEARER: And just to tick off Sarah Palin, you went to Harvard and Harvard Business School, right?

YVES SMITH: That’s correct.

HARRY SHEARER: Were you at Harvard Business School at the same time as George W. Bush?

YVES SMITH: No.

HARRY SHEARER: Okay.

HARRY SHEARER: I know some people who know him from back then who claim that he was apparently much more intelligent then.

HARRY SHEARER: Okay. We’ll leave that for another time. So, you’ve been writing a lot in your blog and linking to other sources on the issue of the foreclosure situation, and anybody who’s following this in the national media would think that, from what the banks have been saying to us about it, it’s basically a matter of sloppy paperwork. You’re writing, and the links that you point us to, suggest something rather different. So what is the state of this situation right now, and what does the legal case Kemp vs. Countrywide tell us about it?

YVES SMITH: You’re correct in implying that the banks are trying to minimize this as an issue. The problem starts in the fact that mortgages are now sold to get them in the hands of investors. You know, a lot of people think of the old relationship where you’d go to the bank, you’d get the mortgage, the bank would keep the mortgage. That really isn’t the way things work anymore for almost all borrowers. You know, you may still go to the bank to get your house loan, but now almost all loans are sold to investors and the way that’s done is they’re bundled together and they ultimately have to get into a little legal lockbox called a trust. It’s like a little separate company. It’s a very passive company. Once the mortgages go in there, it’s really supposed to be the same set of mortgages. They really aren’t supposed to trade them in and out or substitute them. And the contracts that create these things were very specific in terms of what the different people involved in setting up these deals had to do to get the little mortgages into the little lockbox. Now what appears to have happened, on a really widespread basis, in that case you mentioned, Kemp vs. Countrywide, gives a critical bit of proof of it – is that for some reason – you know, and it’s really hard to tell because the banks are very closed-mouthed, but you see the evidence of it coming up in foreclosure cases. We’ve seen a lot of evidence on the ground coming up with people fighting foreclosures, but there’s a lot of evidence on the ground that has suggested that somewhere between, say, 2002 and 2005 the banks quit doing a lot of the things that their very own agreements said they had to do to get the mortgages properly into the legal lockbox called the trust. And the consequences are really serious, because the agreements were also set up in such a way to make it virtually impossible to go fix it after the fact. Now what this case you mentioned, Kemp vs. Countrywide, this was just, you know, one borrower fighting Countrywide, and in some of the court testimony they got an executive from Countrywide – which is now owned by Bank of America, but Countrywide was the biggest subprime originator – an executive from Countrywide who’d been there 10 years saying basically, “It was our practice not to transfer the mortgage into the trust for us to retain it.” And people had suspected this is true, but to actually have somebody say it is basically confirmation of the worst case scenario anybody had imagined.

HARRY SHEARER: And, Bank of America soon in that case rushed to say, “That’s not our policy and that person is working in a whole other part of the business and doesn’t know what she’s talking about.”

YVES SMITH: Exactly. And that’s so “the dog ate my homework” it isn’t even funny. I mean, they served up this witness as Bank of America chose this witness to represent them in this case. Their own attorney made the same admission. A lot of lawyers who are objective, you know, don’t have a dog in this fight, have looked at it and said, “This is just baloney. She’s been there 10 years. She obviously has a significant job in this area. She would know what the practices are in this area.” And separately I’ve heard the same thing independently from other people, that, for example, another consumer lawyer was trying to track down where one of the mortgages was – and there are two legal pieces to these mortgages. Legally the part that has to get into the lockbox is what they call the note. It’s the actual borrower IOU that the borrower signs, that the – you know, they had somehow got into Countrywide, and literally a Countrywide employee walked down the corridor, pulled the note out of the file, which is not where it’s supposed to be if you had followed the contracts, and said matter-of-factly, “Oh yeah, we kept them all here. They’re all here.” So, you know, I have separately heard confirmation of this before the Kemp thing came out, but it’s one thing to have, you know, kind of a mole say this who really might not have the whole picture, versus somebody who’s seasoned and been with Countrywide a very long time and was chosen to be the bank’s representative in a legal case on this matter.

HARRY SHEARER: Now as I read what you’re writing, these mortgages don’t just go from the originating institution into the trust. A lot of them travel a very circuitous journey through a number of different sets of corporate hands – or at least in names of corporate hands, if hands can have names – and that each time the mortgages passed from one set of hands to another it would in ordinary practice go through the county recorder’s office in the county where the house the mortgage is on is located, and there’d be a fee, a recordation fee attached, and by doing what they’ve done, they’ve saved themselves some amount of money. There’s a court case in Massachusetts, I think, where the county recorder says, “Hey, you guys didn’t run your transfers though this office and you owe us $500,000, which doesn’t sound like a lot, times all the numbers of counties in the United States, still is like chump change to banks, though one wonders that they did it to save that. But on the other side of the picture, if I’m not mistaken, one reason that the lockbox as you call it, or the trust, has these specific restrictions on when the mortgages can be in there and you can’t be postdating them and getting them in late is for the tax implications of the trust – do I have that right?

YVES SMITH: That is correct. This is a whole multilayered issue. And that’s why it’s a little bit hard to peel all the layers of the problem back. You’re correct that there are a whole bunch of different motivations for why they skipped these steps, but basically, yes, the overview is correct that it was always a provision in these contracts that it would not go directly from, say, the Countrywide to, say, the trust, but they would always go through intermediary parties because they wanted to establish something called, I hate to say it, “bankruptcy remoteness.” They wanted once the mortgages got into the lockbox, that if Countrywide got in trouble, that people that Countrywide owed money to, or the FDIC, couldn’t say, “Hey, you guys sold it to that trust when you owed us money. You shouldn’t have done this. We’re going to go to the trust and grab it back.” Investors did not want to be exposed to that, and so the way to make sure that no one could go to the trust and grab the mortgage back from the investors was to have it go through several intermediary parties and each time it went through it had to be something called “a true sale,” and there were certain legal requirements for that. But basically, all the agreements say that it had to go through these parties and the note, which is – it’s like a check. It literally had to be endorsed by each party. So if it went from A to B, you’d have to show that A signed it over. And then you had to show that B picked it up and that B signed it over. And then if it went to a C, that C signed it over. And then that it finally went to D. The normal minimum chain was A-B-C-D. So you normally had at least two parties in the middle. That was hassle, and you’re right that the recording fees were a motivation.

The banks used an entity which was set up in the late ’90s called MERS to try to skip those recording fees. That’s part of this question. But yes, that they were supposed to go through this conveyance chain, that they did it to skip recording fees, they did it to save hassle, and they basically appear as a whole industry to have just decided they were going to change their procedures to save money and hassle and never bothered changing their legal contracts. I mean, that’s the crazy part. You know, so they had this huge gap between what they committed to everybody to do and what they didn’t do. And the tax issue, you’re correct, is one of the reasons.

The other reason that this is difficult to fix, because from a tax perspective, the reason they made everything so rigid was that the little legal lockbox was supposed to be passive and the tax laws required that the mortgages had to get in there by a certain point in time that’s basically subject to incredibly limited restrictions. It either had to be in there by the time the deal was sold to investors or, at the very worst across all these deals, 90 days after. And the window – you know, the subprime market died in 2007, three months past when that market stopped is long past.

HARRY SHEARER: Let’s take that detour that you offered for a moment, MERS, which as I’ve been reading about it in your blog is a fascinating little subworld. What do the initials stand for?

YVES SMITH: Mortgage Electronic Registration System.

HARRY SHEARER: And it’s a database of these transactions?

YVES SMITH: More or less. I mean, it actually serves two functions. One of the things it does is to track mortgage servicing rights. So if you’re, you know, the people who are “MERS members,” only “MERS members” have access to it, which basically means servicers, who are the guys who handle the payments every month – you know, they’re the ones who take the money from the borrowers and when they get the money they redistribute it to – they handle all the mechanics of distributing to investors, and they also handle the foreclosure procedure, so they have a lot of administrative duties.

HARRY SHEARER: So services – pardon me just a minute – servicers are the function that the bank used to have when it held onto the mortgage.

YVES SMITH: That’s correct. And typically – some of them are independent. A lot of them are departments within banks, which gets a bit confusing, because you’ve got – you know, for example, you’ve got a bank like Wells Fargo wearing its hat as Wells Fargo Servicing, but it doesn’t own the loan, the loan is owned by a bunch of investors. You know, so you do have people wearing sort of – what? you know, who am I today? – relative to all the different parties. So one role is they keep track of – you know, you punch a particular loan number into MERS and the MERS members are typically the servicers and the foreclosure mills. You and I can’t go to MERS and become a MERS member.

HARRY SHEARER: Aww.

YVES SMITH: Aww. So they keep track of who’s servicing the loan. They also supposedly keep track of who actually owns the loan. The problem with “they supposedly keep track” is that compliance by all of these little servicers is voluntary, and there are no penalties if they are slow to input the data. So, you know, one thing that everybody suspects but again can’t prove is that again when the note was supposed to move through all these intermediary parties, even if it was done – remember there was a period when it looks like this was done correctly – it doesn’t even mean the transfers were properly recorded in MERS. And there are cases – of course, we’re seeing these increasing number of cases coming to light – where the wrong party shows up trying to foreclose, or sometimes multiple parties show up to foreclose, and again, if MERS had any integrity, that should be impossible. So, again, we’re seeing evidence on the ground that the theory of what a great system MERS is versus the practice of how it works is not so hot. And needless to say, ordinary citizens don’t like the fact that in the old world, they used to be able to go down to their courthouse and see who actually held the mortgage. And now the whole thing has disappeared into the bowels of MERS and the public can’t find out what the heck is going on here.

HARRY SHEARER: How many employees does MERS have?

YVES SMITH: Uh, 47, and I think it may be up to 48.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: So they’ve outsourced all the database, I believe, to Electronic – EDS, Electronic Data Systems, so it’s really almost a virtual company and they have this very bizarre corporate structure which has been described as unorthodox to the point of being virtually fraudulent where the MERS members will temporarily put on a MERS hat and say, “Oh, even though I work full-time for _____ – again, say Wells Fargo – I’m going to temporarily be a MERS signing officer and do all these things in the name of MERS even though MERS never paid me a nickel. I mean, it’s just – there’s this whole crazy set of arrangements they’ve come up with which now that people have looked at it, they are beginning to question the legitimacy of a lot of the ways that it does business.

HARRY SHEARER: How many people have signed documents as supposed MERS officers?

YVES SMITH: Well, it’s kind of hard to know, because again MERS won’t tell us, but at any one point in time MERS has over 20,000 signing officers authorized on its behalf.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs) Twenty thousand officers! And 47 employees. If you took it at face value, you’d say that’s a rather top-heavy organization, wouldn’t you?

YVES SMITH: Exactly. Exactly. That’s one of the reasons why this whole arrangement is so questionable. It’s obvious MERS can’t properly supervise these people. And then they claim, “Oh, well, we only give people limited authority. They can only operate in this teeny space, so how could they do any damage?” Well, again, there’s evidence on the ground that contradicts that. For example, they claim that they’ve got electronic procedures so that no one could possibly transfer a mortgage from one party to another without both sides authorizing it. It’s what they call an electronic handshake. Supposedly somebody on one side of the transaction has to authorize it before the party on the other side could move it. Well, you’ve got lots of evidence in courts that MERS signing officers have also shown up as the supposed signing officer on behalf of entities that went bankrupt a long time ago. So it is impossible for the entity that went bankrupt two years ago to have authorized this person to do anything on their behalf. There are lots of cases of that.

HARRY SHEARER: The only person who could authorize something once a corporation is in bankruptcy is the bankruptcy referee, right?

YVES SMITH: You’re absolutely correct.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: And there’s no evidence that this happened. So there’s just so much chicanery going on. That’s why this whole bank position that you talked about at the top of the show, that this is just a paperwork problem, is baloney. I mean, you can say this is technically all paperwork, but that’s like saying the credit card agreement you signed is just paperwork. You know, if you deviate, even slightly, from that, the banks are all over you with a zillion fees. So on the one hand it’s not mere paperwork when it’s your agreement with them. But when it’s their agreement with other parties, suddenly “Oh, it’s mere paperwork. It doesn’t matter if we do it right.” I mean, it’s obvious that they have this very two-tier view of the law, that there’s one set of laws that are provided for as far as banks are concerned, and then everybody else really has to toe the line. But the problem right now is those servicers that we’ve talking about have motivations that are very different from those of the investors. You would think that, gee, the servicers should want to do what’s right for the investors. No, the servicers want to do what’s right for the servicer! And the servicers get paid first. They get – you know, so when borrower pays money through servicer to the investors, if there are any fees the servicer gets the fees first. Therefore, servicer is highly motivated to charge fees. And foreclosure is a really lucrative activity. They get to charge all kinds of fees in connection with foreclosures. So the servicer doesn’t really have a motivation not to foreclose. If anything, they have a very big motivation to foreclose, and it’s hit the point now where investors are being hurt by the number of foreclosures.

This is another piece of the story that’s just NOT getting out in the mainstream media at all. You have the mainstream media, “Oh! The people who are not paying are really evil people and of course foreclosure is the right answer.” This is not the way life works with any other kind of lender in the world. If you have a borrower who has gotten in trouble, the first thing that the lender investigates is whether the borrower has enough income still that they’re better off taking half a loaf than none. This is just prudent limit-your-loss behavior. So that’s why we have, for example, a Chapter 11 process. When companies get in trouble, they first see if they can restructure a deal, have the investors take less rather than liquidate the company. Everybody understands in, for example, Chapter 11 Land, that you liquidate the company only when it’s a complete goner. Similarly, for a lot of – now, not all, but for some high but unknown percentage of borrowers, they could pay a loan at a reduced rate. So now we hit the point where the losses on foreclosure that investors are suffering are literally on average over 70% of the mortgage amount. Now, with 70% losses, you could have a huge cut in the amount that the borrower owes. You could, you could whack the mortgage 50% and the investor would be happy! But the servicer would not be happy. The servicer makes more money, like a little Doomsday Machine, just sort of marching ahead and you know chewing up borrowers and the economy willy-nilly for their own institutional imperative. And so one of the reasons that this kind of litigation may move forward – investors generally don’t like suing, because it’s like, you know, sort of turning harsh light on the fact that there’s a problem. But we’ve got such a big gap between what the investors’ interests are and what the servicers’ interests are and the way the servicers have been behaving, that from the investors’ perspective, suing might be a way to get the servicers to finally take doing mortgage modification seriously. Which is what the investors actually would prefer.

HARRY SHEARER: Now this gets into the administration’s attempt to further mortgage modification to help people stay in their homes and the fact that it’s been pretty much a f– failure is a strong word –

YVES SMITH: Fiasco is another word that begins with F that would describe this.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs) So what’s dual tracking? Is that something that’s contributed to this?

YVES SMITH: Absolutely. Dual tracking means that effectively when a borrower gets in trouble, even though the bank is talking to them about doing a mortgage modification, they are still moving forward with the legal steps to foreclose, and what’s happened is that the servicers have pretty clearly gamed the administration’s lack program called HAMP. I mean, the Treasury even had some bloggers – I was one of them – in to talk to them, and Geithner basically even admitted at the meeting that the Treasury was well aware and embarrassed by the fact that the servicers had gamed HAMP. So the administration is even admitting this in public, which they don’t usually do unless failure is so evident that they can’t deny it. But in any event, so what happens is that of course there were some people who were already in trouble, were already late on payments, but there are a lot of people who heard about these mortgage mod programs who were, you know, under duress, like it’s a real struggle for them to make the payments, you know they could see that if anything even slightly goes wrong in their life in the next year they could be in trouble, and so let’s be proactive, let’s be responsible and proactive and call and see if we can get in this mortgage mod program. Well, again, this is extensively documented. In many cases the bank said, “You have to not pay for us to even consider you for this program.” So they were told to get delinquent. They were told to get delinquent, and then on the 91st day – because usually in many of these agreements you have to be three months delinquent before the bank can take – and again it varies by agreement, but typically it’s 90 days – they start the foreclosure process. And in a lot of states where the foreclosure can happen really quickly, you know suddenly by, you know, Day 120, Day 150, they’ve lost their house. And the bank is still talking to them like they’re going to get a mod! The bank is still talking, leading them to believe that they’re getting a mod. They even have paperwork going back and forth, and yet the bank grabs the house. I mean, it’s just astonishing how many cases there are that this has happened.

HARRY SHEARER: Is that a function, at least in part, of the fact that there are two different parts of the bank handling modifications and foreclosure?

YVES SMITH: Well, in theory that could be the case, but in practice – and some of the banks have used this “the dog ate my homework” and “we didn’t have the systems,” and they all get up and piously swear before Congress that “Oh, well, now we know this is a problem and really we’ve put up a new system to implement this.” If the numbers weren’t so large you could believe this, but the numbers are so large, it just doesn’t add up. I mean, for example, you also had cases of the banks repeatedly losing people’s paperwork. I mean, that was another sort of excuse for the machinery grinding on. I mean, how many times does a borrower have to send paperwork to the authorized number and the bank loses it? I mean, there are just too many incidents of bank screwups that are too similar for this not to look institutionalized to a significant degree.

HARRY SHEARER: And we’ll have more of our conversation with Yves Smith moments from now here on Le Show.

BREAK

HARRY SHEARER: We have a caller on our new megaline. Hello.

JOE LIEBERMAN: Hello, this is Senator Joe Lieberman.

HARRY SHEARER: Hi.

JOE LIEBERMAN: You’ve been talking about WikiLeaks on your program today?

HARRY SHEARER: No, actually, we–

JOE LIEBERMAN: Because I’m, I’m going to have to ask you to stop that.

HARRY SHEARER: We’ve been, we’ve been talking about the foreclosure situation, sir.

JOE LIEBERMAN: Oh. Oh, well, I– I’ve been misbriefed then. Well, have, have a great show. Thank you. Bye bye.

HARRY SHEARER: This is Le Show. We continue our conversation with Yves Smith, author of the blog Naked Capitalism. A name has popped up in your writing that fascinates me. Linda Green.

YVES SMITH: Oh, yes. She’s one of the same robosigners.

HARRY SHEARER: What does that mean?

YVES SMITH: The robosigners physically typically sit at the servicer. They’re typically– sometimes they sat at the foreclosure mills, but usually with the servicers. Typically they’re very badly paid and typically their job is to sign documents all day and literally the stuff would show up on their desk. When this file would show up at their desk, something he had already supposedly prechecked. And they would sign these documents, and the reason this is a problem and why the banks are still trying to distance this as paperwork, is the documents they would sign were in almost all cases affidavits, which meant– and an affidavit stands in trials in place of testimony, and in testimony someone is supposed to swear that they have personal knowledge of a matter. Now for somebody whose files have shown up on their desk and they’re signing literally – there’s robosigners that said they signed anywhere from, the typical numbers are 5,000 to 8,000 documents a month. And they typically often don’t sign. They typically have a rubberstamp, which if you look at these documents you can see signs of wear, like the ink is heavier in the middle and lighter at the end, but –

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: They can’t have personal knowledge of this. These affidavits were clearly improper, and to the extent the robosigner was responsible for anything, they had, the checking that they did was simply that, you know, for example if I’m a GMAC employee signing on behalf of U.S. Trust, I have to sign as this particular title. Just checking that if they were signing for that particular legal entity, that the title that they were signing under was correct.

HARRY SHEARER: So, a robosigner like Linda Green would sign as a vice president of a number of different firms?

YVES SMITH: Vice president, or again, again the title could vary, but vice president would be a very typical title for someone like a Linda Green, who’s making like 12 bucks an hour, or maybe on a good day 15.

HARRY SHEARER: Vice presidents come cheap these days.

YVES SMITH: Yes.

HARRY SHEARER: Do you have a bank account?

YVES SMITH: Uh, yeah.

HARRY SHEARER: So you trust a bank to that extent?

YVES SMITH: Well, I– it’s actually, it turns out, it was a little local bank that was bought by a Canadian bank, so at least I’m not supporting a TARP bank. It could be worse.

HARRY SHEARER: Okay. Um, so what we see is a lot of people in Washington and New York saying, “For the sake of the housing market, foreclosures have to speed up.” This foreclosure thing, when Bank of America and JP Morgan Chase suspended their foreclosures for a month or two, the alarm was being spread that this could seize up the housing market and damage the recovery. What’s your assessment of the situation?

YVES SMITH: That is such an intellectually incoherent position, I don’t even– it doesn’t deserve to be dignified. You’ve seen these statistics. I think the Wall Street Journal’s latest statistic was that the average time from delinquency to foreclosure is something like 478 days? That’s the servicers’ doing.

The servicers themselves are– now some of it is admittedly pile-up in the courthouse because in some states like Florida they’ve now had to implement these things called the Rocket Docket because they have a big backload of court cases that they’re trying to move through more quickly. But sort of X cases like Florida. The banks are not foreclosing very quickly because they have such a huge overhang of inventory, and if the bank takes the house, the bank is then responsible for the local property taxes. And so if it’s going to take a very long time to sell the house anyhow, the bank would rather have the borrower on the hook.

So the notion that– the reason that the administration and other people went on this line of “we don’t want to slow up foreclosures” has much more to do with “we don’t want to create the perception that there is uncertainty about the right to foreclose.” This slow foreclosure was nonsense code for another issue, which is not wanting to raise doubts. The banks themselves have put on the brakes on foreclosures massively, or actually grabbing the house, turning into– they still may be grinding through the foreclosure process to keep their options open, but they want the borrower in the house as long as possible, because the borrower maintains the house to some degree. You know, they make sure the pipes don’t freeze over, they mow the grass, and again they are on the hook for the real estate taxes.

HARRY SHEARER: And meantime, if the house is foreclosed, what happens to the flow of money going to the investors in the mortgage on that house?

YVES SMITH: I’m glad you brought that up, because that’s another reason why the servicers are highly motivated to foreclose. Under the agreements that the servicers have signed, the servicers are obligated to keep advancing money to the investors. So, you know, borrower quits paying, the investors still keep getting money as if the borrower was paying and the servicers’ way to get the money back is through foreclosing. Now of course, you’d say that creates obviously a contrary impulse. The servicer should, in any market where they can sell the house quickly, they should want to grab the house and sell it quickly because then they don’t have to keep advancing all this money.

HARRY SHEARER: Mhmm.

YVES SMITH: Now, again, the contracts are a little better designed than the impression I’m giving says. The contracts actually say that once, you know, a loan becomes sort of – they have different language, but it amounts to hopelessly delinquent. Once it’s pretty clear that the borrower is toast, that they are committed to no longer keep advancing principle and interest. But in practice, first, they never set up their software to stop that, and second the rating agencies have something called servicer ratings. The rating agencies look at the servicers to see if they’re really making their payments on a timely basis. So the servicers are kind of under pressure from the ratings agency also to keep advancing this money to the investors. So the servicers would lose if the investors were actually to succeed in getting mortgage modifications, because if they’ve advanced a lot of interest and principle, they need the foreclosure to get the cash in house to pay themselves back, and then they give what’s left over to the investor.

HARRY SHEARER: (sigh) Okay.

YVES SMITH: It’s a big mess.

HARRY SHEARER: Yes.

YVES SMITH: This is, this is why the industry is trying to say, “It’s just paperwork! Don’t open that box! Really don’t open that box, it’s just paperwork and it’s not a problem!” Because the more you look at it (laughs), the more realize what a colossal disaster this is.

HARRY SHEARER: Now, I’m going to ask you a theory question now. This is, this is complex stuff. We’ve been sort of hacking through the thicket with the aid of your intellectual machete. Most of this material has not been in the consumer media. Listen, I’m as illiterate economically as the next person, if not more so, and it’s been observed by a lot of people that most journalists are as well except financial journalists. Do you think that’s the reason why this material is not in the public discourse at this time?

YVES SMITH: Um, there are several reasons. One is that actually this has the severity of the problem really has come to light only since the robosigning scandal broke out. Before, the people who were aware of the degree of this problem were foreclosure defense lawyers, and they could easily be dismissed because, you know, almost all of these people are either legal aid or pro bono or, you know, retired lawyers who might have been more serious lawyers in the past and are operating in the quasi legal aid sort of fashion – versus banks.

And despite the financial crisis, banks have credibility and banks have access to the media, and most people and certainly most journalists don’t understand that these foreclosure defense lawyers, who frankly do not make a lot of money and would make more money doing almost any other type of law, are actually fairly credible people.

You know, there’s a tendency to think that people who represent little people who are in trouble are like ambulance chasers. You know, the people who, you know, go after car wrecks and disability cases and like that. That these are really a different type of beast legally.

But you had all this evidence piling up in courthouses but still looked anecdotal. Even if you’ve got a large sample, it’s a large sample in a bunch of different very spread out courthouses, and nobody really had the motivation to put it all together until it became – and the robosigning issue legitimated it.

But you still have the battle lines are still very much drawn between the banks, who have credibility and access. Now it’s still the foreclosure defense lawyers and some of the people who are getting voices in these congressional hearings like respected academics who’ve been writing about this for a while, Kurt Eggert, Adam Levitin. You know, I mean there are legitimate people who are coming out in favor of these theories who are taken quite seriously, but really it’s two very different set of parties with very different access to the media.

HARRY SHEARER: Okay. So, so much for diagnosis. Now, prognosis. That is to say, what do we do with this? The “Let’s speed up the foreclosure angle” was, you know, “Well, let’s just let the banks fix the paperwork and everything will be fine, and the foreclosures can start again.” And, as I read you, there was a bill introduced in Congress. I don’t– you can tell me what you think its chances are – that was sort of post facto designed to say anything MERS did is legal. Right?

YVES SMITH: Um.. Language has not been proposed. So it’s been presented in the blogosphere as being much further along than it is. There have been basically some trial balloons floated, but no specific language has been proposed. Every lawyer I speak to who’s legitimate says basically, A) a retroactive fix is impossible. Legally it just wouldn’t fly. And that these problems are sufficiently well embedded. You know, there’s all this historical stuff that MERS has done that even if somebody comes up with a prospective fix, it’s not clear that it’s going to work for, you know, two reasons. One is that, of course, you’ve got historical problems as I alluded, and the second is that they’re seeking to accomplish this through Congress when this is all what they call “dirt law.” This is all state-based real estate law. And there are decades of Supreme Court decisions that say very clearly that dirt law, real estate law, is very clearly exempt from federal intervention. If they tried this, you’d have a massive Constitutional battle which would create uncertainty, which I think is the last thing anybody wants.

HARRY SHEARER: Yeah.

YVES SMITH: So if somebody points out that you try going down this pathology, you could just make matters worse. I don’t think this is going to go anywhere.

HARRY SHEARER: Well, the argument would be, because it’s clearly local government, it’s a Tenth Amendment issue, conservatives would recognize that, and then I thought, well, the argument would be these local transactions entered the stream of interstate commerce through the securitization process. Now, if you’re analysis is correct, basically that argument boils down to it to be a federal problem because there was a fraudulent scheme to enter it in interstate commerce.

YVES SMITH: Yeeeah… I mean, you know, they could try that angle. But again, foreclosures are handled locally. I mean, ultimately you’re talking about the perfection of rights on a local basis. And so I think, as I said, even if they try running this theory, it’s going to wind up being a Constitutional fight. A lot of states are not going to take this lying down, and frankly to your point about conservatives and Republicans – I don’t know that you could get it through this Congress anyhow. I mean, for example, in the first round of the – unfortunately I’m missing – not unfortunately, I’m delighted to be on the show, but I’m actually missing the second round of –

HARRY SHEARER: Oh, I’m sorry.

YVES SMITH: – the banking committee – I know, I’m very happy to be here.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: But in the first round of the Senate Banking Committee hearings on the foreclosure mess, you had Richard Shelby beating up on the MERS guy. I mean, Shelby – of course, you love it when these Congressmen play dumb. Shelby used to own a title insurance company, and he was clearly not happy with MERS. So with a guy like Shelby, who’s pretty well regarded, and in an influential position, not buying the MERS theory, I don’t think this is going to get very far.

HARRY SHEARER: He’s a Republican from Alabama –

YVES SMITH: Yep.

HARRY SHEARER: – for people who don’t follow the Senate intricately. So if you’re prescribing, what’s the way out of this mess?

YVES SMITH: Well, what we really need, as I alluded, is a better process for doing modifications. And that really means deep principle mods. And again we had Orwellian language about the administration’s mortgage mod programs. They talk about permanent mods. They’re five-year payment reduction plans. They are not principle mods. And there’s a lot of evidence that says borrowers are much more highly motivated to try to keep the house if they think they might have some positive equity someday. You know, even if you reduce somebody’s payment, in five years it’s going to kick up and they’re still looking at being severely underwater, even after five years of struggle – how motivated are they going to be to really keep the house?

HARRY SHEARER: And we need research to prove that? (laughs)

YVES SMITH: We need research to prove this! I know, this is intuitively obvious, correct?

HARRY SHEARER: Yeah.

YVES SMITH: So, so, what we need is a better process for people to do the – and of course triage means three, but it’s really bifurcation – who’s viable under a, you know, reasonable – and there may be some variability by state and market as to what reasonable looks like – principle mod. And there are actually organized processes to make this more streamlined. For example, there is a group called NACA, which – the problem is they were probably a little bit aggressive in the way they were doing the consumer budgeting, but they came up with a system where literally they would have what amounted to, I mean “fairs” is probably not the right word because a fair sounds like a happy event, but they would have fairs where servicers would show up, borrowers would show up. Borrowers were told what paperwork they had to have, so NACA would screen the borrowers, make sure the borrower really had the income verification and whatever budget information they needed to have, then the NACA person would sit down, scan the borrower documents into a database, sit down with the borrower and work through a budget. So what their real household expenses were and so they could model out what they could afford in the way of a payment, then they would kick it over to the servicer to actually see what kind of mod they could give. Now with groups like NACA willing to do the heavy lifting that the servicers aren’t paid to do, don’t like doing – you know, there’s already a template for a solution out there that takes the burden off the servicers who don’t want to do that kind of leg work. We then just need to come up with, you know, some sort of templates in terms of – of course, everybody’s going to have to be pressured to do this, but some sort of templates as to what mod levels are appropriate, and this is probably going to come to the state attorney generals. I mean, the Treasury does not want to be out in front of this. The Treasury absolutely does not want to inconvenience life for banks, and that’s because the banks have these very big second mortgage portfolios which if they have to write down the first mortgages, they’re going to have to take more losses on the second mortgages portfolios than they’ve shown to date. So part of the Treasury’s hemming and hawing and acting sort of, you know, doe-eyed about –

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: – why the banks aren’t doing mods is a little bit disingenuous. But there appear to be enough state attorney generals that are on the case, and even though you’ve got 50 and they act like a unified front, obviously some have take this mission more seriously than others. I think there are going to be enough state attorney generals keeping the heat on this that there’s some reasonable – again, nothing is ever certain – there’s a reasonable probability that we might see that as the outcome. I mean, that would be the best outcome that we have finally out of this process, pressure on the banks to do mods for viable borrowers, and then for the borrowers that really are toast, you come up with, they are going to have to give up the house. I mean, the notion that people are trying to fight foreclosures who are underwater is largely urban legend. I mean, there may be a few people out there who are really deluded about their ability to pay, but for the most part, people who are fighting foreclosure typically think they’re a victim of a servicing error, or sometimes it’s somebody in bankruptcy where the bank is trying to grab the house even though they’re in bankruptcy and the bank is supposed to leave them alone and let them negotiate the best repayment plan they can and they can’t touch the house during that period.

HARRY SHEARER: Now you mentioned the Treasury Department acting doe-eyed. Didn’t Treasury Undersecretary Barr just recently announce an investigation of all this?

YVES SMITH: Please.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: I mean, you know, they’ve got something like 11 different groups involved and they’re going in and they’re going to come up, they’re doing this investigation in eight weeks.

HARRY SHEARER: Including Christmas.

YVES SMITH: Including Christmas and Thanksgiving.

HARRY SHEARER: Mhmm.

YVES SMITH: Uh– there’s no way. Oh, and, and he also said, “This is really serious. We’re spending five to eight hours on every loan file.” If you know what you’re doing, it’s impossible to spend five to eight hours on every loan file. That’s an admission that they’re wasting time and don’t know what they’re doing. I mean, it shows that they have not bothered training anybody, and this is an exercise in form over substance.

HARRY SHEARER: Where are the toxic assets that the toxic asset relief program was designed to get out of the banks?

YVES SMITH: The biggest toxic assets were collateralized debt obligations which were, when those bonds, when we were talking about those–

HARRY SHEARER: Mortgage-backed securities.

YVES SMITH: Mortgage securities – they actually had multiple pieces. This gets a little bit convoluted. They were structured – this is why it’s called structured credit – but they were structured so that some people got the money first and that’s how you got Triple A securities, and then only when the Triple A guy got everything he was supposed to get did the guy next in the food chain start getting some money.

HARRY SHEARER: So those are the junior, the senior and the supersenior, which I love.

YVES SMITH: Exactly. So they talk about these different tranches. So what happened with, to get a collateralized debt obligation, is you first had the bonds that were created out of the mortgages. And so you had a Triple A piece of that, right? And then you had the lower pieces. People wanted a Triple A piece. They didn’t really want the lower pieces so much, the riskier pieces, and so a little bit of that would get sold to investors, but mainly they couldn’t sell that stuff. So it’s kind of like the problem you have a pig, right? Everybody wants the bacon…

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: You know, the pork loin. People don’t really want –

HARRY SHEARER: The snout and the lips.

YVES SMITH: The snout, the liver, the hooves.

HARRY SHEARER: Yes.

YVES SMITH: Those get thrown into sausage. So the CDO is kind of the equivalent of security sausage. They would take these unwanted parts and throw them into CDOs and then retranch them. So, again, the first people who got the cash flows out of the CDO could get a Triple A. Now, we discovered later that what they threw into these CDOs was so junky that you couldn’t really get – in the end the Triple A’s weren’t really Triple A’s at all. But the junky pieces went into CDOs. And those ultimately the banks wound up holding a lot of them. That’s why we had such a huge train wreck in the banking system because the banks were – there’s a longer form version of the story that I won’t bore you with, but the short form is that some of the banks were keeping them literally to game their bonus systems. Other banks were just creating them so quickly they couldn’t sell them because they were merely getting sort of routine profit of looking like they were underwriting them and selling them and they counted like – so certain departments got credited for profit even though they were still sitting around at the banks. And then when the music stopped the banks were just long enormous amounts of this paper. Now admittedly some of them went to real investors too around the world, who blew up, but a lot of it wound up at the banks, and so that’s the big reason why we had a banking crisis.

HARRY SHEARER: When you say real investors, those would include European banks, wouldn’t they?

YVES SMITH: Well, actually the European banks were big originators. So some of the banks were – you’re correct – so some of the banks were the smaller – the famous ones were the German Landesbanken. The German Landesbanken were everybody’s favorite big stuffees.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: I mean, they were basically permitted to do everything that a hedge fund would do, but they were run by public servants who weren’t incentivized to really be very smart.

HARRY SHEARER: (chuckles) That’s a lovely way of putting it.

YVES SMITH: So, yeah, they didn’t get any upside for being right, they didn’t any downside for being wrong, and it was perceived to be sophisticated to buy this crazy stuff. So they thought they were doing the right thing, and they were being totally snookered. So, yeah. But it was also the big European banks themselves were big keepers of this. Like, UBS was an enormous one. A couple of French banks. You know, Deutschebank, although Deutschebank claims not to be very exposed. That’s just because Deutschebank’s really big. In aggregate they were very exposed, but they’re such a huge bank they could still not take as big a hit as some of the others.

HARRY SHEARER: Well, so the U.S. banks you say have all these second mortgages on these properties that they’d have to write down and take enormous losses.

YVES SMITH: Right.

HARRY SHEARER: Wasn’t that also the problem with a lot of the toxic assets, that they got a fix in the law that spared them from writing those down, so there’s an enormous amount of stuff the banks have that’s still being valued as–

YVES SMITH: On the one hand the banks are being permitted to carry the stuff they still have at values that most people would say is inflated. And some of that is the supercheap interest rates. I mean, everything on zero percent interest rates, everything looks like it’s better than it ought to be.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: And a lot of the stuff really didn’t trade, so the banks have a lot of latitude in terms of how they value it. The flip side is that some of these CDOs are actually being unwound, that they are being dissolved and the underlying little pieces of mortgage bonds that are in them are being sold in the market. So you do have cases where you’re actually having liquidations and so the banks can’t pretend they’re worth more than they’re worth. So that part of it appears to be being ground through, albeit a bit slowly. I mean the second mortgages – you know, CDOs are a problem, second mortgages appear at this point to be a bigger problem than the CDO problem.

HARRY SHEARER: Okay. Finally, in this area of prognosis, you’ve pointed out that there was a process that we went through in the savings and loan crisis in the 80s, late 80s, early 90s, called resolution. And that clearly was not the process followed during the banking crisis, the credit crunch, whatever we want to call it, of 2008. Is that something that we should have done, should still want to do?

YVES SMITH: Absolutely. It would be – the problem now is you have so many policymakers who would not be willing to admit that what they did in 2008 and early 2009 was wrong, that unfortunately I see the odds of us doing down that path as being quite low.

HARRY SHEARER: What is resolution?

YVES SMITH: The typical model is you find some way to get the bad assets out of the banks. That usually means, if the bank has enough bad assets, that it has to be put on some form of life support which is receivership. Unfortunately that got branded as “nationalization,” which suggests, you know, Communists seizing productive businesses, as opposed to euthanizing something that’s on its last legs anyhow. You therefore strip out the bad assets and you find some way to liquidate them over time. You have a sort of disciplined process for figuring what they’re worth and figuring out, you know, how you’re going to get buyers to bid on this stuff and just clearing the crap out. You take what’s left, the better parts of the bank, and you get that back into private hands as quickly as possible with new management and with a new board. One of the critical pieces of this is that you make it very clear to executives that run bad companies that they don’t get rewarded. And typically in a resolution process you would fire the executives for cause. I don’t care what anybody says about this nonsense about executive contracts. There is such a thing as firing people for cause, and the excuse that we couldn’t do that, and we couldn’t have found legal theories under which we could have revoked these ridiculous severance payments, is to me just not credible.

HARRY SHEARER: A lot of the S&L guys landed up in jail.

YVES SMITH: That’s correct. I mean, that would have been another way to handle it. Basically, you know, you want to fight us on severance? You know, you might get an orange jumpsuit out of this.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

YVES SMITH: You know, they would have backed down quickly if somebody had tried that line seriously.

HARRY SHEARER: So does this suggest that the S&L guys for all their influence, for all their contributions to both political parties during the heyday of the savings and loans – didn’t have the political clout that the leaders of the big four or big five banks have?

YVES SMITH: That’s absolutely correct. I mean, they were – even though Keating famously boasted, I think, that he owned five senators. Five senators is not enough (laughs) – it’s not a majority!

HARRY SHEARER: Yeah.

YVES SMITH: So yes, unfortunately, you know, the financial services industry is the second biggest contributor to congressional campaigns. Only the healthcare industry is bigger. And probably more impo– I would say as important if not more important, is the way that they have penetrated the regulatory infrastructure. You know, you both have the explicit influence, you know, via sort of Government Sachs, via the revolving door, how many people go from public service into cushy private-sector jobs with banks. You had the other level that the regulators, even the ones who think they’re public servants? Like, I have to say, even though, that I honestly think, as much as I have no sympathy with anything, any of Geithner’s positions, I honestly think he thinks he’s doing the right thing. Which is what makes him so persuasive to the media. That he is so drunk – that there are people like him who have so drunk the industry Kool-Aid, that they’re more effective spokesmen than people who are cynical.

HARRY SHEARER: Mm. Well, this has been fascinating to me to try to follow all this. Obviously people get paid an awful lot of money to think this stuff up.

YVES SMITH: Well, no, it’s true. And the sad part about this is that this system was really well designed. I mean, and it did comport itself well for – ehh, you know, more than 15 years until people started abusing it. I mean, this really is a massive self-inflicted wound. And for the industry to try to say that it was somehow innocent or somehow these were mistakes is just baloney.

HARRY SHEARER: One little follow-up question. You said the securitization of mortgages has been around for 20 years, but yet it exploded in like the 2000-2002 time. What was the ignition for that explosion?

YVES SMITH: Well, that was the supercheap interest rates. I mean, this was sort of effectively part of policy. I mean, you remember that Greenspan had been actually encouraging people to take adjustable rate mortgages, arguing that they were a better deal for consumers than fixed rates. You know, we had had a long period of overly easy consumer credit as the solution for the fact that worker wages were stagnant. If you look at a sort of a longer-term time chart, you see it starting in the 1980s you have consumer debt to GDP increasing gradually over the 80s and then dropping a bit in the S&L crisis, you know, the late 80s, early 90s recession. Then you see it increasing a bit more gradually in the early 90s, and at 1999 shoot to the moon. I mean, you just saw consumer debt levels – it was primarily mortgage debt – just shoot to the moon. Um, so, how could anyone not have seen this happening? I mean, there was all kinds of press about how, for example, the consumer saving rate was zero. It was hovering around zero and it even certain quarters was negative. How could the Fed not see that this was a problem? And yet they came up with all these complicated rationalizations. It was unfortunately a very bad combination of super-low interest rates that induced everybody to pile on more leverage and regulatory inattention to the irresponsible behavior that was taking place.

HARRY SHEARER: And for the consumers, debt was being sold as well.

YVES SMITH: That’s correct. And there were a lot of people who, you know, some people were completely naïve and some people allowed themselves to be conned, but if you’re a young person and you see housing prices escalating and you’ve been told, people were told for 20 or 30 years that renting is stupid and buying is smart, you’re going to be afraid, “Oh my God, if I don’t buy now, I’ll never be able to buy a house. I’ll be a renter for my life, and that’s a really horrible thing.” You know, so there really was, as much as some people overextended themselves, there was also very aggressive promotion of this notion of home ownership.

HARRY SHEARER: Mhmm. I really want to thank you for lending your expertise and your ability to kind of make this pretty comprehensible to the lay person such as myself. I really appreciate your time.

YVES SMITH: Well, thank you so much. I really appreciate the opportunity. Thank you for giving me so much time.

HARRY SHEARER: Yves Smith, author of the blog Naked Capitalism – sounds sexy – and of the book ECONned. Thank you so much.

YVES SMITH: Thank you.

Closing music

HARRY SHEARER: Just a little bit of news from outside the bubble that non-newsworthy WikiLeaks stuff included revelations that the United States pressured Germany to knock off prosecuting anybody who was involved in the extraordinary rendition of a young man named El Masri, a totally innocent man who was bundled off to Syria and tortured. And conservatives in the United Kingdom, before they were elected to office, promised the United States that there would be among other things more pro-American weapons procurement. Damn those French armament makers anyway! Oh, sorry, Senator Lieberman. I’ll knock it off.

Ladies and gentleman, that’s going to conclude this week’s edition of Le Show. The program returns next week at this same time over these same stations, and it’ll be just like resolution, if you’d agree to return with me then, would you? All right, thank you very much, uh huh, thanks to Henry Perotti at Howard Schwartz Engineering in New York, Nick Kray at De Lane Lea Studios in London, and Adrian Bodenham here at Global Radio in London for help with today’s broadcast. Le Show is on Twitter @theharryshearer.

Le Show comes to you from Century of Progress Productions and originates through the facilities of KCRW Santa Monica. Santa Monica? Come on! You’ve heard of it. You know it well. It’s a community recognized around the world as “the home of the homeless.”