12.10.12

12.10.12

Transcript: Nicholas Shaxson Interview

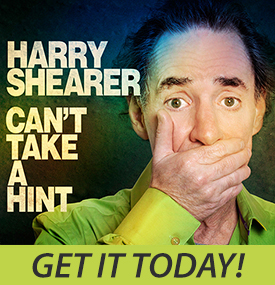

HARRY SHEARER INTERVIEWS NICHOLAS SHAXSON

OFFSHORING GOES ONSHORE

LE SHOW, DECEMBER 2, 2012

Listen to the podcast here.

From deep inside your radio.

HARRY SHEARER: This is Le Show, and we’re not in tax season yet. We’re in gift season. But taxes are on the minds of at least some folks in London, where I’m recording this broadcast. There has been a great deal of attention in the newspapers and the news media in the last couple of weeks to the tax affairs of multinational corporations such as Google, Amazon and Starbucks. A parliamentary committee held hearings the last couple of weeks and there has been a great fuss made about whether these companies are in fact paying what, a term of art we would use as “their fair share” of taxes. And this put me in mind of a book on the subject of multinationals and taxation that I read a couple of years ago, and it is still incredibly relevant to what’s going on now. And so my guest today is the author of that book, NICHOLAS SHAXSON. The book is called Treasure Islands. It’s available both in the United States and in the U.K. And Nicholas is joining us from his home city of Zurich, Switzerland. Welcome.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Hello, thank you.

HARRY SHEARER: Thank you. What made you take on this subject and write this book?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well, really it was a couple of things. There were kind of like moments of illumination for me. Several years ago I was confronted with evidence that the offshore system of tax havens was so much bigger than I or perhaps nearly everybody imagined. I think in the popular imagination it’s always been a kind of, you know, these tax havens have been a sort of exotic sideshow to the global economy; they’ve been places where a few kind of, you know, mafiosi and celebrity tax dodgers and a few bankers go and stash their ill-gotten gains. But I began to see that this system was actually much, much bigger and much more central to the global economy than I’d ever suspected.

One of those moments of illumination came when I was talking to a U.S. lawyer and he was explaining to me that the United States itself had over the last few decades been turning itself into a tax haven. In other words, providing secrecy facilities to foreigners to attract hot money from around the world and essentially trying to kind of copy Switzerland and copy other tax havens to bring all this money into Wall Street. And not only that, but he was saying that the U.S. had had this kind of under the radar as a central pillar in its strategy to finance its external deficits.

And that conversation told me two things: One, that the geography of tax havens, that tax havens weren’t where I thought they were, not just the Cayman Islands and places like that, but the United States itself, and I subsequently found out my own country, the United Kingdom, arguably even more important, the most central player in the system.

So there’s the geography of tax havens, but also the size of it. I mean, this is absolutely huge stuff we’re talking about. The offshore economy has been growing much faster than the supposedly onshore economy for decades, and as a result it’s grown up to something of absolutely enormous proportions.

HARRY SHEARER: So when we hear tax havens, is there any justification for – these are, let me, let’s get definitional for a minute. These are jurisdictions, whether they’re Jersey off the coast of Britain, or Cayman Islands, notoriously, where tax rates are quite low and corporations may appear to locate some or all of their most important business affairs. Is there any – in the literature of the folks who defend tax havens, is there any rationale for their existence, beyond hiding from taxation in a home country?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well, first of all, I want to – this definitional aspect is actually very important indeed. Tax havens are – you know, I tried in Treasure Islands to drill down into what exactly is it these places offer. And, you know, tax, the name is a little bit of a misnomer. Tax is certainly an important aspect of what they offer, but there’s a lot more to it as well. I mean, secrecy is another part of it. And there are various other aspects such as financial regulation, escape from criminal laws – all these different aspects sort of come together in a package in these places, in these – you know, they tend to be large, important financial centers.

And drilling down to what, you know, what this package is all about, I eventually got down to the bedrock of two words. And one is this word “escape.” So, you take your money elsewhere and you escape from domestic rules at home, whether those rules be tax laws or whether they be financial regulations or whether they be criminal laws or whatever. So there’s this issue of escape from the rules of society that bind most people, and usually it’s the wealthiest elites in a society that can escape.

And the other word is “elsewhere.” So you’re taking your money to another jurisdiction. And with that taking your money elsewhere, you know, effectively the lines of democratic accountability are cut.

So the laws of one jurisdiction of the British Virgin Islands or the Cayman Islands, for example, are not designed directly for the benefits of the citizens of those small jurisdictions. They are designed to target, you know, the business operations and citizens of the United States, of Latin America, of other parts of the world. And these laws are made in consultations, in kind of small, private consultations with insiders, and they’re not made in consultation with the U.S. public or the citizens of other, you know, of Latin American countries. And so there’s absolutely no kind of democratic accountability for how these laws are made. So that kind of almost from a definitional point of view, you have a problem there. This is kind of an anti-democratic system right from the outset.

Now you asked a second question about, you know, what are the defenses that tax havens make for themselves. Well, there are a series of defenses that are put forward that I believe, you know, all of them kind of fall apart once you unpick them.

One of the defenses is that, I mean a common one is of course is that taxes are bad and anything that helps you escape taxes is good. And, you know, you can have a whole debate about the relative benefits of taxes and how high or low they should be, but I – and I, you know, I deliberately try not to sort of say that taxes should be higher or lower or whatever, I just think that, you know, democracies need to decide what level the taxes are at. But that’s kind of a debate one can have, so, from a defense of tax haven point of view.

Another very common defense is that they make the international financial system more efficient. In other words, they help capital flow around the world more smoothly. They remove obstacles from the path of international financial flows. And I’m very deliberately using the word “financial.” I’m not talking about trade here, necessarily. Of course there’s a relationship, but I’m talking about capital flows, financial flows. And that sounds great. You know, efficiency, who could argue against efficiency? But, again, if you unpick that, you work out that, you know, what are these obstacles that are put in the way of international financial flows? And you know these obstacles are things like tax, are things like financial regulation, things like criminal laws. And these places kind of strip these things out, you know, and in a sense that does make it more efficient in terms of the actual free flow of movement, but that doesn’t necessarily make the whole system more efficient, and that’s kind of one of my big beefs with tax havens.

HARRY SHEARER: That language sort of dates from an earlier era where countries would oppose capital flight restrictions to strengthen their national currencies, doesn’t it?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well, yes. I mean, there’s a whole chapter in Treasure Islands looking at the period after the Second World War, the kind of quarter century that followed the Second World War roughly. That was a period when there was a great, kind of, you know, under the Bretton Woods cooperative international arrangements, there was a kind of agreement to heavily restrict the cross-water flow of capital, and this was kind of as a result of the lessons learned from the Great Depression when there had previously been, you know, financial deregulation and, you know, wild cross-water capital flows, and a realization that these could actually be harmful for economies.

And so after the second World War, it was a kind of unique period in history, they put into place these very tight controls on the financial sector domestically in the United States on Wall Street and so on, and to a lesser extent in the U.K., but also these kind of controls on cross-border flows of capital. And that period of what’s known as financial repression was actually the greatest period of growth world-wide in history. And this was broad-based economic growth. This was not the kind of growth we’re seeing, we’ve been seeing in the last few decades, where a lot of people at the top are getting hugely wealthier and most of the middle classes are kind of stagnating. This was really broad-based growth with, you know – many people call it the Golden Age of Capitalism now, and that was a period of tightly restricted financial flows. And the period –

HARRY SHEARER: So we wouldn’t want, we wouldn’t want that.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well – (laughs) The thing is, I mean something like that, it’s kind of politically impossible to imagine these days. I mean, you’ve had huge advances in technology. It’s – you know, how would you return to such an age? And people also say that, you know, correlation isn’t causation. You can’t prove that those restrictions are what caused that high growth. But you can say that it is quite possible to have very high growth amid very tight restrictions on the financial sector and cross-border flows.

And you are seeing now the IMF and other bodies that, you know, previously it would have been complete anathema to even mention a word such as “capital controls” controlling the flow of finance across borders. They’re beginning to timidly mention it. And there has been a real sort of reassessment in light of all that’s happened in the financial crisis of, you know, these kind of tools and whether they could be useful again.

HARRY SHEARER: Let’s get a sense of perspective. I think in The Guardian newspaper this very day, there was an estimate of the amount of money that’s involved in the offshore economy –

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Yeah.

HARRY SHEARER: – and it’s in the low trillions? Would that be correct?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well, again, because nobody agrees on what a tax haven is, there’s no definitional agreement, all these estimates are subject to, you know, a lot of leeway. But there was a very influential report put out a few months ago by the Tax Justice Network, a U.K.-based group, estimating that the amount of assets sitting offshore range between 21 and 32 trillion dollars. That’s trillion, not billion.

HARRY SHEARER: Mmhmm.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Which, you know, if you look at sort of total estimates of world financial wealth, that’s kind of 10% or 15% of the total. So it’s a very significant chunk. Again, you know, those numbers are subject – you know, what is a tax haven, what is offshore, nobody agrees, so you could make a lot of estimates in different directions. But we’re talking, we’re talking many trillions of dollars, that’s for sure.

HARRY SHEARER: We’re talking real money, as they say.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: We’re talking real money, yes.

HARRY SHEARER: So when, when did all this start? I mean, when did – who set up the first tax haven, and when was it?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well, the offshore – I mean, in a sense offshore has always been with us. I mean, going back hundreds of years, it’s always been possible to take your money to another country where, you know, your rulers can’t, you know, see at all. You know, it’s invisible to people at home. The first real big tax haven was Switzerland, and in fact even before Switzerland came together to become a country. It was a place that for various reasons has been not only very stable politically – they’ve kind of, because they have a lot of divisions inside Switzerland, they set up these very clever constitutional mechanisms to kind of deal with conflict, and that has created a very stable society. And also its neutrality; it’s historically been a neutral country. And that has meant that when there’s been, you know, times of turbulence, you know, conflict, the First and Second World Wars, you’ve seen huge flows of money into this kind of stable, uh, uh –

HARRY SHEARER: Safe haven.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Safe haven, exactly.

HARRY SHEARER: Yeah.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: And with the latest financial crisis, you’ve seen a lot of that as well. I mean, it’s not conflict-related, but it’s, you know, Greeks worried about their country being ejected from the euro and all that kind of stuff, so you’ve seen this flight to Switzerland. There’s been huge amounts of money coming in, and the Swiss central bank’s been buying up very large foreign exchanges there to kind of stem the, you know, the currency appreciation.

And so that’s kind of – you know, the safe haven aspect of it has been always very important. But that safe haven aspect has also come with the fabled Swiss banking secrecy, which back in 1934 it was kind of enshrined in law. It was already a kind of de facto tax haven. People already knew that Swiss bankers were going to take their secrets to the grave, but in 1934 it was enshrined in law. This was in response to some banking scandal in France that this happened. And since then, Swiss bankers have kind of been very influential in the politics and made sure that secrecy has been a kind of bedrock of Swiss society ever since.

So Switzerland was kind of really the first, the first big one. But then you had – when the period of globalization started in the, you know, kind of from the ’60s and the ’70s especially onwards, you had a kind of second system grow up that I would describe as sort of the Anglo-Saxon system, which fundamentally Britain was the most important part of this. And it was a kind of slightly different. Rather than Swiss bankers who, you know, stayed quiet, secretive, sitting with vast kind of stores of wealth in the Bahnhofstrasse here in Zurich, you had kind of much more high-octane Anglo-Saxon finance running through these tax havens, and there was a lot more kind of getting away from financial regulations, and – but also secrecy’s an important part of it.

And Britain is – as I describe it in Treasure Islands, there’s what I call a spider’s web where essentially you have the City of London right at the center, and around it you have this series of kind of concentric rings of tax havens. So you have tax havens like Jersey in the English Channel. You have tax havens like the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Gibraltar, so even today they are so-called British Overseas Territories. And they’re kind of half in and half out of Britain. They’re partly controlled by Britain, their governors are still appointed by the queen, but they have their own independent politics. And outside of that there’s another, you know, whole ring of Commonwealth Countries which are tax havens. And this kind of network acts as a sort of feeder system. So it’s kind of grabbing business and the business of handling money from around the world and feeding it into London, into the City of London.

So that’s kind of, for me, the second big aspect of it. And of course the United States is a sort of third major component of the system. And they’ve grown up – the two latter ones have grown up very much, very substantially, in the last few decades.

HARRY SHEARER: Now, for Americans, the concept of the City of London is a strange one. It is not to be confused with the metropolis that we know as London, England. It’s a very special part of it. And in your book there’s a lot of revealing information about what the City of London actually is and its particular peculiar legal status. So could you go into that a little bit?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Yeah, I was really astonished when I researched this bit about the City of London. And this is stuff that very few people in Britain knew about. And, you know, it’s getting a little bit more attention now. But the City of London, in the popular language it means a couple of things. First of all, it just means U.K. financial services, the sort of international finance center. And that’s, quite often, when people just talk about the City, they’re talking about all this money coming into Britain. But more specifically, there is a jurisdiction inside London which is one of the local authorities. It’s geographically right at the center of London. It’s very small. It’s only got about I think at the moment 9,000 people living in this small borough. It’s known as the Square Mile as well, as it’s slightly larger than one square mile. And this is where the Bank of England is and, you know, the headquarters of major banks. And this local authority is known as the City of London Corporation. And it’s a completely unique body in Britain. It is a local authority, but it’s unlike all of the others. It is also officially a lobbying organization for the deregulation of finance. I mean, you will find them saying this, and for keeping finance deregulated in the United Kingdom and internationally. The City of London has a Lord Mayor who is not to be confused with the Mayor of London, currently known as Boris Johnson.

HARRY SHEARER: Boris Johnson.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: The Mayor of London looks after, you know, 10 million people, and the City of London Corporation, the Lord Mayor, he’s just responsible for a few thousand, for 9,000 or so. And it has its own very strange constitutional position inside U.K. as a local authority. Elsewhere in Britain, you know, people just vote and vote in the, you know, local elections, but in the City of London corporations are able to vote as well. It’s a remarkable fact. And corporations get a vote allocation according to how big they are.

HARRY SHEARER: So this is the reification of Mitt Romney’s famous dictum that corporations are people too.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well (laughing), in a sense, yes. And this has been going on for, you know, hundreds and hundreds of years. I mean, this is an ancient – they call themselves the world’s most ancient constitutional democracy. They say, you know, there’s no record of the corporation actually coming into existence, the City of London Corporation.

And it is also this incredible sort of old boys’ network, and it’s full of these old livery companies, which are old trade associations, but they’re still very much alive, and many of the top people in the professions, in various different professions, are members of these livery companies. So you have, as of a few years ago, the Worshipful Company of Tax Advisers, which (laughs) contains some very powerful people in it. And these livery companies are dedicated to supporting the Lord Mayor of the City of London, whose role is officially to support the deregulation of finance. It sounds extraordinary. I mean, you know, when I was writing this, I was kind of worried I was going to sound like some sort of, you know, conspiracy nut writing about it, but it’s just there, you can go and look at, you know, the City of London Corporation. Go and look at their website and have a look what’s in there. It’s remarkable.

HARRY SHEARER: How does it relate to the regulatory structure of British law generally? Are they under it, totally? Do they have – have they carved out exemptions?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well, they are not the regulators for the financial center. The City of London Corporation is not the regulator. But they are incredibly influential. And they’re influential through this kind of old boys’ network that is, you know, incredibly pervasive. And they have – you know, they stand heavily on ceremony and the Lord Mayor goes around in these gilded coaches and they have these banquets and, you know, they have sort of fingers reaching out, and legislation that’s, you know, that’s passed will have had a lot of attention paid by the City of London Corporation. And the corporation has an official who is known as the Remembrancer who sits in the British Houses of Parliament and he kind of monitors legislation that’s out there and, you know, watches out for, you know, populist attacks on finance and things like that. (laughs)

And so they’re very influential. And it’s very hard to quantify, I mean, just how powerful they are. I mean, they say, “Well, we’re just a sort of funny old, you know, group of people, and we – ”

HARRY SHEARER: “We’re quaint.”

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Yeah, exactly! I think they hide behind their quaintness. But they do put out these regular reports, you know, kind of saying, you know, “The City of London is losing its competitiveness, there’s too many taxes, too much regulation” – these reports just come out like a drumbeat, and quite often the newspapers just kind of parrot them, you know, they just say, “City of London say London is losing its competitiveness,” and then all the politicians get frightened and say, “Oh, we mustn’t tax them too – tax the banks too much.” And so it’s a very curious phenomenon. It’s unlike anything else. I mean, it’s something that, you know, an economist will not be able to get their heads around this thing, and political scientists find it hard enough. It’s just a very curious sort of anomaly, but a very important one.

HARRY SHEARER: We’ll get back to the role of London in the offshoring phenomenon, but there was an article in the, I think in the Washington Post a couple of years ago, before I even read your book, that first opened the door to part of this world, which has, as I said, since become better known through the parliamentary inquiry into Google, Amazon and Starbucks, which is a tax avoidance scheme, as they call it in Britain, without the derogatory implication that it has in the United States, called the Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Mmhmm.

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Yep. (laughs)

HARRY SHEARER: Could you walk us through that?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well, this is, that one is actually quite a common one. I think there was a good Bloomberg report that looked at that particular one. So essentially you will have multinationals looking to find pathways through the international tax system that result in them paying very little tax. And there are lots of jurisdictions. I mean, Ireland and Luxembourg are two very, very important tax havens. Most people don’t really think of them as tax havens, if people – most people we don’t really think about Luxembourg at all –

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: – but in Europe it is very, very important. And Ireland – you know, the Irish Financial Services Centre is a great big kind of Wild West area of deregulated finance that has actually, if you looked deep into it, it’s got a lot of implication in the latest financial crisis, a lot of Wall Street stuff was parked there. And, you know, the Netherlands is another big one, Switzerland is another big one, the United Kingdom is another big one, where multinationals basically are looking to cut their tax bills.

And the way they do this, generally, is each multinational is treated by the international tax rules as a collection of separate entities. They have subsidiaries all over the world. And these entities trade with each other. And they can adjust – these are internal trades inside the multinationals, and they can adjust the prices of these trades to suit their tax bills.

So what they can do, for example, a tax haven subsidiary will buy something from another subsidiary of the multinational – maybe it’s a cargo of bananas or something. This is all happening on paper. It’s not – the bananas aren’t actually going to that tax haven. So they will buy a cargo of bananas at a very cheap price and then they will sell that cargo onto the U.K. subsidiary or the French subsidiary at a very expensive price, and so they’ve bought cheap and they’ve sold expensive and they’ve made a huge profit, and that profit is now sitting in a tax haven, because that’s where that entity is, and it’s untaxed. Meanwhile, in the U.K., where they’re selling it on, they will sell that cargo at a very, very high price to a retailer, so there’s no profit in the U.K. there to tax. And a similar thing, when they’re buying it from, you know, Ecuador, the cargo of bananas from Ecuador, they’ll buy it at a very low price, they’ll buy it basically at cost price in Ecuador. So they’ll tell the tax authorities in Ecuador, you know, this is how much we sold this cargo of bananas for and it’s the same price as the cost, so there are no profits there. So what you are seeing here is you’re seeing profit shifted from both the sale and the production end into the tax haven, and that’s the sort of essence of the game.

And, you know, countries do take – there are all sorts of countermeasures that countries do take against this, and it is a constant dance between the countries and the multinationals, but developing countries in particular find it impossible to challenge these incredible – you know, they will find themselves faced with armies of lawyers and accountants and there’s just nothing they can do. And particularly companies with, you know, intellectual property. If you have – you know, you can locate a company’s brand or a logo in a tax haven and then you say it’s worth this much, and the tax authorities try and challenge that, and, you know, how much is Coca-Cola’s brand worth, or how much is Google’s brand worth? Well, you know, it’s really worth what the company’s accountants will say it’s worth, and it’s very difficult to challenge.

So you have an international tax system that is incredibly dysfunctional. It was kind of set up decades ago and it just hasn’t kept pace with globalization.

HARRY SHEARER: One would think that if the Peace Corps were still – the Peace Corps is still in business, they might want to be sending armies of lawyers to developing countries to really help them out.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well, that’s an inter– that’s actually, what you’re talking about there is there is a fledgling organization being set up. It was originally conceived as something called Tax Inspectors Without Borders –

HARRY SHEARER: (laughs)

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: – which is exactly what you’re suggesting. And I know that the OECD, the group of rich countries, has taken this idea on board. I don’t happen to know where it’s running with it. But this would be, this is exactly a very good idea indeed and I hope it becomes a great success. Another thing that we’re just beginning to see happening is people talking about running training courses for journalists to try and – particularly in developing countries, to try and help them understand how to look at the offshore system, how to understand it and how to investigate it. And so these are just kind of new initiatives that are just bubbling up and I think that, you know, they could go a long way to helping expose what’s going on.

HARRY SHEARER: Well, let’s talk about your background for a minute. Before you delved into this subject, what were you doing? Were you –

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well, I spent –

HARRY SHEARER: Are you a journalist, an economist, or – ?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: I’m a journalist by background, a sort of economic and financial journalist. I spent many years writing about oil-producing countries in Africa. I wrote a book called Poisoned Wells that was published in 2007 that was the result of nearly 15 years’ work of going, you know, visiting these countries, and I spent the whole time trying to understand why it was that these countries were not realizing the benefits. So you had countries like Nigeria, Angola – hundreds of billions of dollars flying into these countries, and yet the people of these countries just, you know, seemed to be as poor as any other African countries. You know, it was a very sort of depressing time to spend. I mean it was very interesting, of course.

But over that time when I was researching it, academics were beginning to put together this thesis, this set of research that nowadays goes by the name of the resource curse. In other words, many countries that find minerals like oil seem to not only find it hard to harness them for national development but in some cases seem to be even worse off than if they hadn’t found anything. And I strongly believe Angola, the country that I know best, which is a big oil exporter, really has been cursed by its minerals, oil and diamonds, and if they hadn’t found any I think their people on average would be much better off than if they’d just been, you know, a nonresource country.

But one of the most interesting things about this is, having moved, made the transition from oil, the resource curse, to tax havens and financial centers, I began to see so – I have seen so many similarities in terms of the political dynamics. Countries that are dependent on finance, like the U.K., are also finding it terribly hard to harness all this money. There’s trillions of dollars coming in and out of the City of London and huge sums of, tides of money coming into, you know, the U.K. property market and stuff, and yet you look at the sort of real human development statistics for the U.K., you know, infant mortality and health outcomes and things like that, and the U.K. is doing, you know, it’s doing worse than France or Germany or, you know, other countries that, you know, with which you could compare it.

And a lot of the reasons for this, I think, are quite similar. I mean, you have a single dominant sector – in Angola’s case it was oil, in the U.K.’s case it’s finance – sucking all the best talent out of the rest of the economy, out of both the private sector and the public sector, and focusing it on this one single sector. You also have, you know, exchange rate effects where, you know, the dominant sector will raise price levels, making it much harder for other sectors to compete.

And all these kinds of factors add up to what I am increasingly beginning to call a finance curse. You know, and this goes way beyond what most people are angry about, what’s happened on Wall Street and what’s happened on the City and all this financial crisis stuff. This goes way beyond that. This is something much more fundamental. This is something that was afflicting countries long before the economic crisis, the financial crisis came along. So this is a thesis I’m kind of currently developing and I’ll be publishing something on this early next year.

HARRY SHEARER: Okay. We’ll await that. In the meantime, you mentioned among your list of tax haven type countries one that may surprise a lot of listeners, i.e., the United States of America. Now I last year happened to be in Wilmington, Delaware, for a couple of days, and I walked through downtown Wilmington, a downtown festooned with a lot of tall buildings with the names of banks on them, and at midday I think I was about one of three people walking the (laughs) streets of downtown Wilmington.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: (laughs) Okay.

HARRY SHEARER: And I thought, what’s in these buildings if not people?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Yes, Wilmington’s a fascinating little place, and it’s got its own little financial center, and that results from – the main sort of impetus for that was the so-called Financial Center Development Act of 1981, and this was initially a project to essentially offsh—what I regard as offshore activity, poaching activity off other states by deregulating. You know, it’s a kind of race-to-the-bottom activity. And at the time there were strong curbs on interest rates and, you know, what banks could charge, the interest rates.

HARRY SHEARER: You mean the so-called usury laws.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Yeah, the usury laws, exactly. And essentially there was a court case in which it became clear that individual states were allowed to export their own interest rates to other states. They were allowed to roll out, you know, credit card operations or whatever and use them in other states, use the same rules in other states. So, I mean, South Dakota tried to be the first to get on this bandwagon but South Dakota’s, you know, quite off the beaten track compared to Delaware, which is halfway between New York and Washington D.C., and so Delaware got onto this one and it created this Financial Center Development Act.

And what really struck me about it was, you know, I researched this in detail and I had a very good researcher working with me, and we discovered that essentially this was a project that was done with absolutely no local consultation. There was a small group of insiders who decided they wanted this thing. There was no consultation even with the population of Delaware, let alone the states that were going to be affected by all this legislation. It was a deal that was done. The Democrats were brought in on it. It was a Republican governor at the time but he brought the Democrats in and the Democrats agreed not to make any noise about it until after the election. And it was a deal that was just kind of presented. It was created by the finance industry and there was no, there was just no democratic consultation.

And, you know, that’s kind of my main point. I mean, one can argue about whether or not usury laws should have been repealed or not, but – and, you know, some people argue that it has been a very negative thing. But the thing that struck me was just this kind of small, kind of – it was just like what I’d seen in other tax havens. It was just small groups of people coming together in private, talking to the financiers, “What do you want, we’ll give you what you want, and that’s it, and we’ll make the laws and no one will need to know about until we’ve created the laws.” And in these very small jurisdictions you have, you know, usually there’s not very much expertise and people just essentially saying, “Okay, we trust you on this. You know, you’re going to make this legislation; we don’t really understand it, but, you know, we’ll vote for it, that’s fine.”

And, you know, I saw exactly the same thing in other tax havens. It’s just the sort of small jurisdiction mentality where finance comes in and gets what it wants and no questions are asked really.

HARRY SHEARER: But this grew out – Delaware had always been, or had long been a, a prime site for incorporations, right?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Yes.

HARRY SHEARER: That didn’t start in the –

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: That’s another – yes. And that’s another important aspect of it, yes. So Delaware has always been, for over a century, been a prime site for incorporations, and that is offering a slightly different package there and that’s particularly to do with corporate governance. So you offer corporate governance services that are particularly favorable to managers, often at the expense of shareholders, and that encourages corporate managers to incorporate there, and it’s just a kind of very simple business model. You relax your laws and the money will come.

And there are many types of reasons that companies incorporate in Delaware, but one of them is secrecy. And this is part of what I was talking about earlier, the United States as a secrecy jurisdiction. The U.S. offers secrecy both at a federal level and also at a state level, and Delaware corporations – and Delaware’s not alone; Nevada is another one, Wyoming is another, and there are various others. States offer secret corporations. In other words, they will allow you to set up a corporation for just a few hundred dollars that provide extraordinarily strong secrecy, in some cases as strong as Swiss banking secrecy.

And they do this through a completely different route. They do it by allowing you to set up a company with nominee shareholders and nominee directors. And so, you know, these people who are nominees, they will be the directors of hundreds if not thousands of companies, and you can find out as much information as you like about these people, but that brings you no closer to the real warm-blooded person who owns that corporation. Those people, you know, the real owners, the beneficial owners, will stay secret.

And there has been a lot of dirty money running through all of these corporations, and drugs money, and so on, and there’s been quite a lot of noise about it recently. But still, you know, the lobbyists have managed to say, “Oh, it’s going to be difficult. It’s inefficient to make us, you know, have more onerous due diligence requirements to check up on, you know, who owns these companies.”

So still, you know, there’s a lot of work to be done to clean up this sector. Delaware is, you know, is a massive provider of state-level secrecy through its corporations.

HARRY SHEARER: Now recently I’ve been reading about, in Yves Smith’s Naked Capitalism blog, among other places, about a blossoming of this kind of stuff in New Zealand.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: (laughing) Ah, yes. New Zealand is a kind of – there are so many tax havens around the world that seem to have this sort of blemish-free existence, and New Zealand has the distinction of being ranked as the cleanest country by Transparency International (laughs) at the moment. But if you look at some of the things they’re providing – I was looking at this recently, and Naked Capitalism is a site I visit regularly and enjoy very much, and they helped give me a tipoff in a couple of cases here – but New Zealand has a couple of different strings to this particular bow.

One is, again, secret corporations. There have been investigations into – you know, you have these little houses. There’s a house in Auckland that’s just sitting there with thousands and thousands of corporations in filing cabinets, and no information, and the government’s not asking them for any information, and all sorts of – you know, they’ve been linked to all sorts of nasty, you know, East European mafia and drugs money and stuff.

And New Zealand also has a trust sector. Now, trusts are another whole can of worms. Offshore trusts in particular can be very slippery creatures and very – again, very, very strong providers of secrecy. And New Zealand trusts have been implicated in all sorts of, you know, Mexican drug money and stuff like that.

And so here you have this country that has, you know, in many cases it has a very clean reputation and yet on the other hand it has this incredibly dirty financial thing going there.

And that’s the same of many jurisdictions. I mean, you know, the City of London tries to portray itself – you know, U.K. – people generally regard the U.K. as a very warm and friendly place and British as trustworthy and it’s got very strong courts and legal system and, you know, all this sort of stuff, stuff is true, but on the other hand you have this kind of ocean of dirty money that sits alongside this, you know, all this probity. And it seems like an incredible paradox to have these two sitting side by side.

HARRY SHEARER: In the final moments, and I’m speaking with NICHOLAS SHAXSON, author of Treasure Islands. In the final moments we have together, there are some efforts by some governments to exert what might be called tax transparency upon all this stuff. How’s – who’s on what side of that?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Well, there are a series of measures going on. I mean, the biggest and most important are, there’s one project that’s going on in the European Union and there’s another project going on in the United States that are the most serious efforts. Now the U.S. effort is kind of a unilateral thing. It’s protecting the U.S. tax system from offshore erosion. And the United States has been very fierce. It in recent years has had a huge fight with Switzerland in particular. They’ve caught – the Justice Department has had cases against Swiss banks and they’ve caught them red-handed helping Americans evade taxes with all sorts of colorful stories about, you know, hiding diamonds in toothpaste tubes and, you know, poaching, you know, going to the America’s Cup and trying to, you know, just looking for customers and helping them, you know, get their money offshore.

So, you know, that kind of thing has really stuck in the public craw and the Obama administration, under the Obama administration there’s been a certain, you know, a fair degree of attack on Switzerland in particular, but also they have this legislation coming in, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, which requires foreign financial institutions to identify any American clients that they have and pass information about their assets to Uncle Sam. So that’s a kind of unilateral U.S. thing. It’s an interesting and sort of positive development, but it’s not – and the U.S. is kind of pushing, you know, this out to make it more reciprocal with other countries.

So that’s one – you know, it’s kind of, I see that as one pillar of an emerging architecture.

And another big pillar is the European Union, it’s got this scheme going which is currently full of loopholes but it’s essentially an information-sharing mechanism as a way governments share information with each other about their wealthiest citizens’ assets and income so that they can tax each other properly. And, you know, it’s geographically limited to there are 42 jurisdictions in here, but it’s – I see this as a sort of the first stirrings of something new, of an emerging architecture of transparency which is still in its early stages and still, you know, full of holes and, you know, still not raising huge amounts of money, but it is new. It’s the start of something new.

And I think with governments, you know, facing austerity and looking for tax revenues everywhere, I think the political momentum behind this kind of thing is really growing now. And I think, you know, there’s a long way to go and I think there are positive things happening.

HARRY SHEARER: To close, let me go back to where we were at the beginning. There has been a lot of publicity about Starbucks in England and Amazon in England making significant profits, to some eyes, and yet paying negligible income taxes because of tax-avoidance procedures that are strictly legal under current English law. And there’s been talk about boycotting these companies. If you lived in England, which you don’t, would you be patronizing or boycotting Starbucks and Amazon?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: I’d be boycotting them, because, for the simple reason – I mean, this defense they come up with, “It’s legal, so it’s fine,” it doesn’t hold water. For various reasons. One is, when you’re talking about corporate tax affairs, you are talking about an incredibly complex arena, and between the legal and illegal there is a large gray area, and these corporations operate frequently in this gray area, and you only find out which side of the law they really are on once there’s been a court case, the tax authorities have taken them to court and you get a resolution one way or the other. So, you know, there’s a question – you know, how aggressive – the question is how aggressive are these companies going to be, and it seems that Amazon and Starbucks have been particularly aggressive, you know, pushing into this gray area where it’s not quite clear. You know, you certainly can’t say they’ve broken the law, but you can’t say either that they haven’t broken the law, and it’d be interesting to see what the tax authorities would say.

But more fundamentally, I think, you have corporations that are coming in to the U.K. and taking all the benefits, the services, the infrastructure, the well-educated work forces, the rule of law, the courts, all these fine things which are all paid for out of tax dollars – they’re taking these things and then they’re making their profits and not paying for the services. And that is something that sticks, and it’s a very simple thing, it’s something you can get people in the streets very angry about, and it makes me very unhappy to see this happening.

And even worse than that, perhaps, these corporations are competing with domestic companies that are doing, trying to be in the same business but they’re being killed by the multinationals on this factor, tax, which has nothing to do with real productivity, with real economic efficiency, nothing to do with making better, you know, goods and widgets and services, but everything to do with transferring money away from others, transferring wealth to them from others. And there’s nothing productive at all about this. This is simply a gigantic distortion in the market. And, you know, so it’s profoundly, it’s damaging to – you know, it’s – in a sense, this whole thing is anti-business, even though multinationals are getting lower tax rates, they are harming, you are harming domestic businesses, smaller, more local businesses, which are often the job creators and the innovators, and they’re being killed on this as a result of this gigantic distortion.

So it’s a huge problem, and it’s not – you know, hiding behind there saying, “Well, it’s all legal,” is just not going to work.

HARRY SHEARER: NICHOLAS SHAXSON, I highly recommend Treasure– is the American version the same as the British version?

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: It’s pretty similar, yeah. It’s essentially the same, though it’s a little bit shorter, but –

HARRY SHEARER: (Laughs)

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: It’s essentially the same, yeah.

HARRY SHEARER: Treasure Islands is the book, and it’s fascinating. The story of offshore in all its ramifications which continue to this day. Thanks so much for sharing your time with us on today’s show.

NICHOLAS SHAXSON: Thank you. Great to talk to you.

HARRY SHEARER: You too.

Now, ladies and gentlemen, the Apologies of the Week. We won’t even ask why the American version is slightly shorter than the British version. Now to the Apologies of the Week….

That’s going to conclude this week’s edition of Le Show. The program returns next week at this same time over these same stations, on NPR Worldwide throughout Europe, the USEN 440 cable system in Japan, around the world through the facilities of the American Forces Network, up and down the East Coast of North America via the short-wave giant WBCQ The Planet 7.490 MHz shortwave, on the Mighty 104 in Berlin, around the world via the Internet at two different locations, live and archived whenever you want it at harryshearer.com and kcrw.com, available through your smartphone through stitcher.com, and available as a free podcast at kcrw.com. And it’d be just like us getting to offshore our profits too if you’d agree to join with me then. Would you? All righty, thank you very much, uhhh huh.

A tip of the Le Show chapeau to the San Diego, Pittsburgh, Hawaii and Chicago desks for help with today’s broadcast. Thanks as always to Pam Halstead. Thanks also to Andy Stallabrass at De Lane Lea studios in London and Tom Wenger at Tom Studio in Zurich for help with production of today’s broadcast. And thanks to the Chicago desk for being right here in New York. Is it you who left the toilet seat in the ladies’ room up? Yeah. That’s what I thought.

The e-mail address for this broadcast and the playlist for the music heard hereon is part of the welter of new stuff at harryshearer.com. Hey, there’s a store there now! You can buy Unwigged and Unplugged, you can buy my little comic novel Not Enough Indians, and if you’re in Chicago Tuesday night at Space in Evanston, Judith and Harry’s Holiday Sing-along benefiting the New Orleans Musicians Clinic with a lot of great Chicago musicians. Please come and support a good cause.

This broadcast is represented on Twitter. Join the more than 77,000 followers @theharryshearer.

Le Show comes to you from Century of Progress Productions and originates from the facilities of KCRW in Santa Monica, the community recognized around the world as The Home of the Rubber Promise and The Home of the Homeless. Put that seat down now!