08.18.15

08.18.15

New Orleans – flood, failings and fears for the future

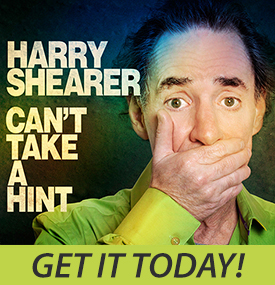

Ten years on from Hurricane Katrina, Simpsons star, satirist and actor Harry Shearer reflects on the flood that devastated his home town New Orleans – a topic he explores in Archive on 4 documentary New Orleans: The Crescent and the Shadow.

Harry Shearer: I was born in Los Angeles, but I fell in love with New Orleans – it’s as simple as that.

I was in Los Angeles ten years ago when Hurricane Katrina passed 35 miles northeast of my New Orleans home. I was acting in a movie called For Your Consideration. When not on camera, I was glued to my devices, gleaning every shred of information from a city drowning in flood water.

My friends there had called or texted to say they were OK, or were leaving or were on the road. One was able to visit our condo a few days later and manage the biggest job for those whose homes had not been destroyed – getting rid of the refrigerator which, starved of electricity, had been storing food at temperatures of 38C (100F). The streets were lined with refrigerators for weeks.

I followed the news on local New Orleans radio and television, but also watched the US networks that were keeping most of America updated. But were they telling an accurate story? Well, the first inkling I got that there was a problem was the day after the flood. A reporter from CNN was standing in a place I recognised as the central business district, but his opening words were: “I’m here in the French quarter.”

The incident revealed several problems about modern journalism. One was the hollowing out of American print and broadcast media. The front page or anchor remains, but behind them now is a smaller group of people who parachute into any news location, talk to a couple of cab drivers, and get on camera to tell viewers what “the mood here tonight is”.

To my eye, only one of the hordes of people who covered this story for the broadcast media either lived in New Orleans or understood the geography. What we saw on television were horrific pictures of African Americans trapped in these shelters of last resort – the Morial Convention Center and the Louisiana Superdome Arena, which were close to off-ramps of a major interstate highway and easily accessible for TV trucks. What we didn’t see were pictures from the suburban county ten miles east of the city, where working class, white people had been on their roofs for four days with no food or water.

Levee breaches

The broadcasters probably didn’t know that place existed, but it meant the flood became characterised very quickly as a racial story – something that happened to poor black people. The responses – even in a liberal publication like the Huffington Post – were highly coloured by that perception and the political will to do something about New Orleans was, I think, equally coloured by that perception. In fact, the calamity was something that happened to everybody – 80% of the city was flooded.

I live in New Orleans, I know the city and I was there when all the news people left. They’d covered four of the five tenets of journalism – the who, what, where and when – but had departed without telling people why the flooding happened. It means that some people still regard it as a natural disaster when, in fact, independent investigations by two universities concluded that the devastation was caused by more than 50 levee breaches and failures. The studies point the finger of blame at the US Army Corps of Engineers, which built the protective system.

We ask in the Radio 4 programme if lessons have been learnt in the past decade. The answer to that is not heartening.

New Orleans is a tropical city and it had to devise an effective way of pumping out water. There can be fearsome rain, but I can walk out into the street ten minutes later and it looks like it never happened. The water runs into canals which empty into the lake, but a hurricane storm surge can raise levels in the lake and return the water to the city via the canals. That’s what flooded New Orleans ten years ago. The walls of the canals failed and they haven’t been repaired. The US Army Corps of Engineers argues that gates will close between the canal and the lake in a hurricane scenario, but if too much rainwater accumulates in the canals – and with no escape for it back into the lake – I believe those walls will fail again.

Opportunity for change

The flood of 29 August 2005 led to the uprooting of virtually everybody in New Orleans, at least temporarily. It was an occasion – if not an opportunity – for an awful lot of other things to change, some for the better and some for the worst. 100,000 people who were evacuated – most of them poor African Americans – never returned. Statistically, it’s a less poor city than it was; it’s still a majority black city, but less so. Politically it has gone from black mayor, black majority council to white mayor, white majority council. These kind of changes stimulate an awful lot of opinion-making on one side or another.

Tourism is back where it was, though, and the city has become a Mecca for the entertainment business, especially television and movie-making. New Orleans is even starting to outpace Los Angeles for production of major – so-called Hollywood – features. I shoot some of my own stuff there, including a documentary on which I used a New Orleans crew. These are jobs that didn’t exist in New Orleans ten years ago. It’s become a great place to work.

Life has returned to something resembling normal. I was born in Los Angeles, but I fell in love with New Orleans – it’s as simple as that. It starts with the people and the culture in which they live.

We hear the word community a lot these days in reference to bunches of far-flung people with a common interest, sitting around their computers. New Orleans is an actual community. To come from a normal American city – very atomised and very individualised – to a place with this tightly-knit fabric of community is to realise how different it is.

That’s one reason why the disaster was worse in some ways for New Orleans than it would have been for a ‘normal’ American city. Some of those whose parents or grandparents drowned in their attics, trying to escape the water, are still haunted by what happened and cannot return. The tightness of that tapestry of community was totally rent asunder by 2005’s flood.

Archive on 4: New Orleans – The Crescent and the Shadow is on BBC Radio 4, Saturday 22 August at 8pm.